by Sofia Kotilainen

In 19–23 August 2024 I had a privilege to participate the 28th International Congress of Onomastic Sciences in Helsinki. It was inspiring to hear and see so many great presentations of colleagues. They introduced plenty of new perspectives to onomastic research.

Theme of the multidisciplinary conference was Sustainability in names, naming and onomastics. I have studied the history of inherited first names in the Finnish rural families. Recently, I have started to conceptualize these findings and results of my earlier research. Using the concept of onomastic literacy has proved to be fruitful in reaching the mentalities of the people and local communities studied.

Onomastic literacy means the knowledge and skills the parents of a child need to interpret the local naming culture and communal norms of naming. Parents had to be familiar with the traditions of the family and the locality to be able to choose a ‘suitable’ name. In this respect, names functioned as cultural symbols connected with identities and kin networks.

Honouring the ancestors

Universally, the most common social norm governing the choice of names has consisted in giving a baby a name handed down within the family, mainly the name of a grandparent. Giving the name of a living relative would have detracted from this person’s good fortune as it correspondingly added to that of the younger namesake. And especially in the case of grandparents, it may have been thought that the blessing and luck received by the oldest members of the family would in this way be transferred to the newborn baby. For example, in Finland in the olden days, it was said that a child would turn out like his or her namesake.

There would seem to have been many kinds of religious and social functions attached to the choice of names of ancestors besides honouring them. For example, namesakes might have been thought to hold certain responsibilities towards each other when both, for example a grandparent and a grandchild, lived in a certain community at the same time. It was perhaps possible to perceive in the child family traits or a resemblance to a forebear, after whom the parents then might wish to name him or her. Behind this way of thinking can be perceived an ancient Finno-Ugric belief about the soul, according to which a child who receives an ancestor’s name also inherits his or her persona or soul.

This then was the case when a child was named after a dead relative. The child was in this way symbolically connected to the earlier bearer of the name. It was believed that when for example the first-born boy in the family was given his grandfather’s name, the latter would in some way continue his life in the new member of the family. Even though the belief had spread into Scandinavia in the pre-Christian era, it continued to exert an influence later. It has been assumed in earlier research that in Finland, too, the relics of such naming traditions can be perceived right up to the twentieth century.

Inherited first names in the Finnish rural families

The above-mentioned conceptions of the early modern beliefs and mentalities that regulated naming, were based on oral memory accounts that were mainly used as a source in ethnological research rather than on the systematic empirical use of written documents as sources of historical research. However, with the help of extensive collective biographical databases, for example, and by utilizing the genealogical method, it is possible to examine to what extent traditional beliefs any longer influenced naming practices from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries and were realized in it in practice.

In all ages an inherited family name has played an important part in the shaping of a person’s identity. Particularly in the pre-modern age, a personal name also made rural people a part of a family community and defined their place in it. In the agrarian society of former times, the traditions of the family were respected. The networks between relatives also formed an economic and social safety net on which a person could rely. Inherited names were also associated with a feeling of the continuity of the family and traditions. That is why it was important to name a child after his or her grandparents or parents because in the name-givers’ world view it bound a child and his or her future into the enduring immaterial heritage of the family.

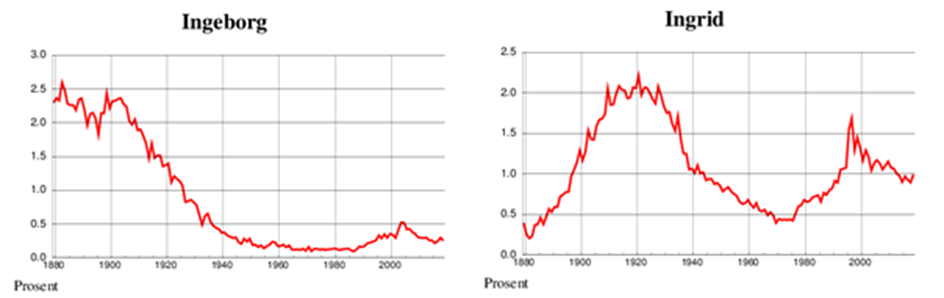

The practices of naming did not change sharply in the shift from the early modern to the modern period, and many interacting cultural layers from different periods continued to influence naming practices in an essential way. The relics of ancient practices and beliefs were preserved to some extent right up to the twentieth century. A more exact analysis of local naming practices using a variety of document sources and collective biographical databases shows that, regarding inherited names at least, the modernization of naming practices took place slowly. They were affected not only by the local living conditions of the community but also by the complex and asynchronous effects of the modernization of society.

Recycling the names

Family traditions, being grandmother’s or grandfather’s namesake, or having name of a valued member of the family community, were signs that name-givers, i.e. usually parents of the children being culturally ‘literate’ and honouring the elder generations in Finnish rural local communities. This created sustainability and good reputation of the first names of the forefathers and -mothers, as they were inherited from generation to generation.

Onomastic sustainability has been important for the development of social traditions, values, identities and intergenerational relations. Local naming traditions change slowly and may influence naming practices of several generations. Active reusing the names keeps the cultural heritage alive.

See also:

- Kotilainen, Sofia 2022. Utilizing the concept of onomastic literacy as an analytical tool: a methodological examination of the names of European royal families. Nordisk tidskrift för socioonomastik / Nordic Journal of Socio-Onomastics 2, 73–104.

- Kotilainen, Sofia 2012. An inherited name as the foundation of a person’s identity: How the memory of a dead person lived on in the names of his or her descendants. Thanatos 1(1), 1–24.