by Line Sandst

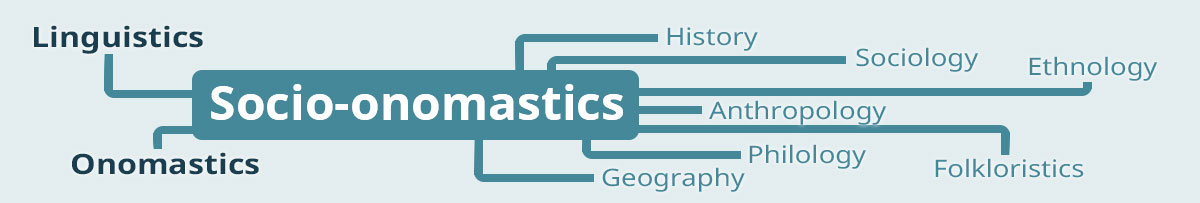

My socio-onomastic research focuses on urban toponomy and meaning-making. I am particularly interested in the modalities and socially constructed geosemiotic conventions that enable language users to distinguish between different grammatical categories (e.g. between proper names and appellatives) – and therefore different kinds of meanings – in the linguistic landscapes.

As assistant professor of Danish Linguistics at Aalborg University, I teach a diverse group of subjects from Danish phonetics, to rhetoric and theories of argumentation to language history. However, I have also experimented with a more direct kind of research-based teaching in socio-onomastics for MA students, as I outline below. I share my thoughts on my teaching practice in the hope that others might benefit from my experiences. Please do feel free to share your viewpoints, experiences and give feedback so we may all benefit from an exchange of ideas.

Teaching objectives

When teaching socio-onomastics from an urban toponymy point of view, I find it important that the students gain experience from actual field studies. I put together a curriculum of texts that can be divided into four overall topics: an introduction to onomastics, methodology, current socio-onomastic studies, and theories of names and naming and other theoretical problems depending on interest, such as multimodality, geosemiotics, language policy etc. During the course, we discuss the texts on the curriculum, but I also spend time helping the students to come up with a relevant research question/problem, and prepare them for conducting fieldwork.

Finding a research question is usually the hardest part for my students. The socio-onomastic scholarship on the curriculum serves as a framework and inspiration for them to come up with their own research questions and designs. I encourage them to find a problem that sparks their academic curiosity as I find that a personal interest is the best motivation for academic work. However, for those students who find it hard to come up with a question, I present three examples of possible studies for inspiration:

- Investigation of commercial names in the linguistic landscape: Pick a street or an area of town and take photos of the commercial names in the study area. What do you find? (Possible angles depending on the data could be (one or a combination of) e.g. multimodal names, names that do not conform to expectations, names coined in other languages than Danish. Do you find any patterns or tendencies? Are you able to say something about the identity of the study area based on the commercial names?)

- Investigation of recent street names: Pick an area where there is a construction project under way. Take a walk in the area and take photos. What kind of identity is being created? Do the new names fit the area? How come/ why not? You may even compare your findings to relevant architectural drawings and building contractors’ documents containing ‘visions/narratives’ about the area’s future identity.

- Investigation of the relation between commercial names and street names: Pick an area with theme based street names and take photos of the commercial names and street names in the area. How many – if any – of the commercial names have a name that fits the theme of the group named area? Are you able to say something about the identity of the area based on the relation between the two name categories?

I encourage my students to work in groups or pairs because it enables them to discuss and solve the problems that might occur during the data collection and later in the analysis process. I find that when students are held responsible to each other, they are less inclined to give up if they are confronted with unforeseen obstacles, or if they find the task at hand hard to complete.

In class, I spend time discussing research questions and research designs with each group and make sure they have a clear idea of how to conduct the actual fieldwork. When interpreting proper names in the linguistic landscape, the researcher always needs to consider the context thoroughly. This is why I encourage my students to take pictures of the proper names as well as other objects they might find interesting in the field, and I instruct them to take field notes during the field study. This makes the subsequent analysis and interpretation much easier.

Presenting the data and results

In the last session, each group has to present their study for the class and I instruct them to present:

- Research question

- Presentation of data

- Possible sources of errors / limitations

- Analysis and results.

All listeners have to give constructive critique to their fellow students on their fieldwork and studies. Since all students will have fieldwork experience themselves, I find that they are very capable of asking relevant and constructive questions to the studies conducted by their fellow students. Asking the students to offer criticism to one another gives them a unique possibility to reflect upon others’ as well as their own role as researchers. If necessary, I direct the discussions and ask them to relate practice to theory. I sometimes ask how they would have conducted their study, if they had to do it all over, in light of what they have learned through our discussions. My students tend to have already considered the methodological implications of their own practices, and asking this question allows them to reflect further on their study as the first step towards an improved or perhaps different empirical study based on fieldwork – hopefully one with a socio-onomastic point of departure.