By Krister SK Vasshus, PhD-student at the University of Bergen

Many modern Scandinavian names have a deep linguistic history, and they come in many shapes and forms. Helge, Torkil, Arnhild and Inger are just a few examples. Names of this type all have in common that they are based on words that carried a semantic meaning at the time when they were formed. They could be formed based on verbs (such as Wīgaz from a verb meaning ‘to fight’), nouns (such as Aud, meaning ‘wealth’), or adjectives (such as Braidō, based on the adjective meaning ‘broad’). Most of the names used during the Scandinavian Iron Age and Viking Age are no longer in use today, but many are still fairly popular. Some of these names have even gotten more popular over the last two centuries due to the popular interest in the Old Norse literature and culture.

Names of Scandinavian origin can be formed based on one single word, often with the addition of a suffix. Examples hereof are Arne (meaning ‘eagle’), Karl (meaning ‘man’), and the above mentioned Wīgaz. But they can also be compounded from two words, such as Sigrun, Ingeborg and Wōdurīdaz. Names based on two words are often called dithematic personal names. The oldest written evidence we have of Germanic languages is written on a bronze helmet with Etruscan letters, dated to about 200 BCE, and this inscription contains the dithematic name Harigasti (‘warrior-guest’).

Even though names are formed on the basis of words from the source language, it may some times be impossible to determine what the original meaning may have been. A view commonly held by researchers of onomastics, is that the semantic content of a personal name deteriorates quickly after being used as a name. According to this view, Wōdurīdaz was not a wild and angry (which is the semantic meaning of wōdu-) horsebackrider (the semantic meaning of -rīdaz), and that his parents did not give such a name with the intention of giving these qualities to the child. Not all scholars agree with this, though, and some think that names may be seen as a linguistic expression that conveys the same ideas as we see in other artistic expressions of the time, such as metaphors used in skaldic poetry or ornaments on archaeological artifacts. As an example, the warrior-ideal was quite strong in the Viking Age, which is reflected in many names containing words connected to war and battle. Many of the animals we see in the arts, are also used in personal names of this period.

Judging from runic inscriptions, sagas and traditions up until now, we can see that Scandinavians have three ways one could name someone after another person. Today most people will probably think of naming someone after someone else as the two bearing the same name. Stereotypically this means that a child is named after a grandparent. This type of naming tradition first shows itself in Scandinavia during the Viking Age, and was probably adopted from elsewhere in Europe. The system usually is that the oldest child is named after their paternal grandparent, the second oldest child is named after their maternal grandparents, the third child after their paternal great-grandparents or uncles and aunts. It can, however, be difficult to determine whether a child is named after an aunt/uncle or a great grandparent, as these would share names according to the system.

Another way of naming was by alliteration, where the name starts with the same (or a similar) sound. This is a type of naming we see in the royal Yngling house, where Domalde, Domar, Dyggvi and Dag follow each other in succession. The same dynasty later uses vowels: Aunn, Egill, Óttarr, Aðils, Eysteinn and Yngvarr. This tradition is still in use today, although people are probably a bit more strict on using an identical vowel.

The third way of naming is the principle of variation, which can be used in the dithematic personal names. When a child was named, one could use naming elements that were otherwise used in the same family. This means that a person could be named after more than one family member at once. On the Upplandic runestone U1034 we can read:

þorbiarn·auk·þorstain·uk·styrbiarn·litu raisa stain·eftir·þorfast·faþur sin ybir reisti (Thorbjørn and Thorsteinn and Styrbjørn raised the stone after Thorfast, their father. Øpir carved [the runes]”).

Here we see that Thorbjørn and Thorsteinn are named after their father, as all their names starts with Thor-. Furthermore we see that the brothers Thorbjørn and Styrbjørn share the naming element Bjørn, but we cannot determine whether they are named after someone else in their family, or if it was made to show brotherhood.

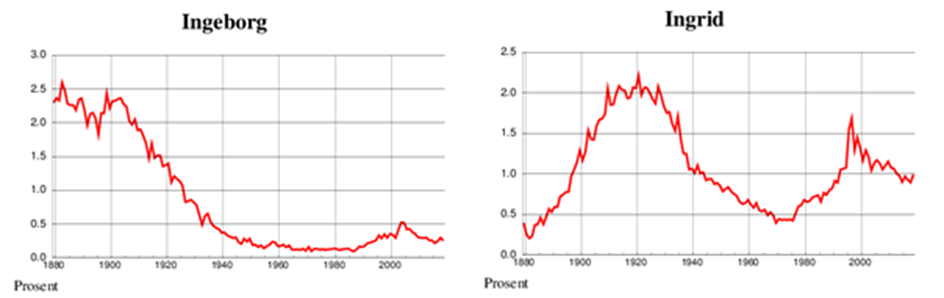

This way of naming is still in use in Scandinavia today, and many new names has been made on the basis of this principle (some examples are Kjærlaug, Norunn, Vilfrid, Tryggvald, Norulv and Bjørgny). This principle lead to a substantial amount of dithematic personal names. Gjrotbjørn, Ljotunn, Igulfast, Ulvhild, Geriheid and Wōdurīdaz are examples of names that has gone completely out of use, in contrast to Ingeborg, Bodvar, Gunnhild, Sjurd (from older Sigurd), which has survived to this day.

Exactly why some names survive and some fall out of use, is sometimes difficult to determine. In some cases it may come down to chance, and in some cases we see that a name may live for a long time but only in a very constricted region. And although kinship plays a much less important role in the modern Scandinavian society compared to in earlier times, the naming traditions still show that to some people, it still plays a role.